From Gene Logsdon

Excerpt from Practical Skills 1985

In his fascinating book, The Farm and the Village (Faber Paperbacks, London, 1969), George Ewart Evans points out that the village blacksmith of the 6th to 17th centuries found himself very much in demand if he could make a hoe blade thinner than those of his competitors without sacrificing strength. The reason was simple enough. Not only would a thinner blade slice more easily into the soil, but more importantly, it would weigh less, by at least a couple of ounces. To people who hoed for 10 hours a day all week, a couple of ounces made a big difference.

I can appreciate that observation, since in addition to normal garden hoeing, I hoe ½ acre of corn twice during May and June, and I hoe dock, thistles, and other weeds routinely from an 8-acre pasture field. The only hoe I’ve been able to find to suit me is an ancient one I bought years ago for 50¢ at a farm sale. This hoe is so old that about a third of its original blade is worn completely away, and what is left is not half the thickness of a new hoe blade. Light, its edge sharpened well, the hoe does not tire me nearly as much as new ones, and the fact that the blade is smaller by a third means I can maneuver it between plants in the row much more easily.

I have bought three hoes since then, so that all the members of the family could join the weeding, but we all grab first for the old hoe. Two cheap hoes from the hardware store are, by comparison, almost repugnant to us, and everyone cheered when the handle on one of them broke. They are too heavy. The blades are too thick and blunt, requiring much grinding with a heavy-duty bench grinder to reshape the cutting edge properly. And after so much grinding you run the risk of ruining the temper in the blade. Most of all, the angle of the blade to the handle is all wrong; in drawing the hoe toward you, too much of the flat side of the blade breasts the soil, increasing the drag or draft needlessly.

The best new hoe I have found, for my body anyway, is the “field hoe” [or “grub, digging, eye, or azada” hoe available from EasyDigging.com]. Though still heavier than my favorite old hoe, it is, at 2 1/3 pounds, light compared to most hoes. I like the way the blade fastens to the handle. The blade has a hole in it to receive the handle directly, making it what is called an “eye” hoe, or Scovil-type, after the principal manufacturer.

Most common hoes have a blade connected to the handle by a slender steel neck stuck into a ferrule and are called shank hoes, or (better) a one-piece neck and socket into which the handle fits, called a socket hoe. In both these cases, it is difficult to replace the handle. With eye hoes, however, it’s easy to change handles, and the handle, being fatter at the blade end, is not as likely to break. Though the blade slips off easily, the action of the hoe in use binds it tightly to the end of the handle, requiring only a simple nail to hold it in place.

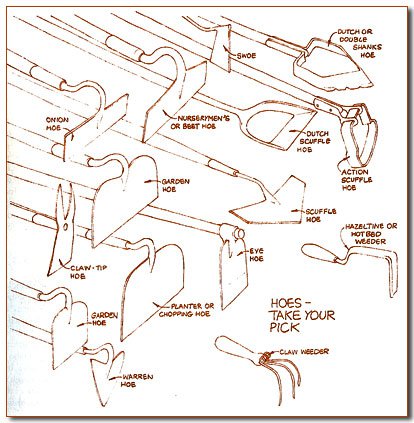

The hoe is one of man’s most ancient tools, and true to its definition as a traditional tool, it is still commonly in use and always will be, as long as gardens are cultivated. Over the years many different hoe designs have been tried, the names proliferating almost as much as the hoes themselves: chopping hoe, hilling hoe, scuffle hoe, onion hoe, beet or nurserymen’s hoe, Yankee hoe, Canterbury hoe, Dutch or double shanks hoe, grub hoe, Hazeltine hoe. The names are more colloquial and regional than standard, and you must look at the hoe first rather than the name it’s been given.

Short-Handled Hoes

These are usually called hand weeders rather than hoes. They are for doing fine work between very small plants, down on your hands and knees. I’ve seldom found a hand weeder that will take the place of fingers in good, loamy, humusy soils. The little three-pronged claw weeders are next to useless, although like most gardeners, I had to buy one before I was convinced. They look effective. I’ve never had a “Cape Cod Weeder,” but John Withee, writing in Farmstead magazine (“Hoes for Hard Rows,” Vol. 4, No 2, 1977) says it is “an overrated, overpromoted, poorly designed toy.” I have tried to use the short-handled, triangular wood scrappers that are somewhat like the Cape Cod, but these tools aren’t very effective on wood either, in my opinion.

Long-Handled Hoes

Many blades are made for long-handled hoes. The standard garden hoe may have square or rounded shoulders, or the blades may be square at the cutting corners or flared out a bit. Blades only half as long as the standard hoe blade, but as wide or wider, are called nurserymen’s hoes or beet hoes, depending on who is using them. Hoes with even shorter blades, but still as wide, are called onion hoes, although in our part of the country, we tend to think of the real onion hoe as a very narrow but long-bladed hoe, or swoe.

Cultivating Hoes

Hoes with three or more prongs or tines for a blade, like Canterbury hoes and cultivating hoes, have been nearly as useless for me as the little claw weeders, but they may be of value in stonier soils. The heart-shaped, pointed hoes, called Warren or furrowing hoes, make nice little furrows to plant seed in. One kind, called the Swan hoe, has a long swan-shaped neck that enables one to pull the blade almost horizontally right under the soil surface, like the sweep-type blades on large motor-powered cultivators. I see no use for any of these hoes when a rotary tiller is used to cultivate between rows, or when a trusty old common hoe, half worn away, can be used for between-row weeding.

Scuffle Hoes

There are at least three distinct kinds of scuffle hoes. They are made to be pushed ahead of the hoer, not drawn toward him. The Dutch scuffle has two steel shanks running from handle to blade, which is pushed flat, just under the soil. The other common kind has only one shank and socket connecting blade to handle. A third kind, rarely seen today, has the Dutch-type double shanks, but they are welded to the middle of the flat blade, not the back end of it. Thus, the blade could be scuffled backward and forward. Both ends had sharp edges, too, making this a much more useful and versatile tool than the other two. Other push hoes, like the Action scuffle hoe, have narrow looped blades of various shapes and can also be pushed or pulled. As Abraham Lincoln said humorously of other matters: “This is the very sort of thing that people who like this sort of thing are surely going to like.”

Chopping Hoes

The regular garden hoe shape, when in extra large models, is often referred to as a chopping hoe or a planter hoe. The only person I’ve ever seen use one effectively is Harlan Hubbard. Harlan avoids loud gas-guzzlers as much as possible, and he uses his big hoe as a primary tillage tool in his soft soil. But he does not “chop” with the hoe; in his hands it seems just to sink deeply into the soil, loosening it to perhaps 6 inches and breaking it up faster than I can do with a tiller, although not as finely.

Hoeing Know-How

The secret of using a hoe properly is that one should never actually “chop” with it, at least not to the point of raising it more than knee-high. If the blade is sharp and angled properly, you can set it on the soil, and, by pulling it toward you with a downward pressure of your arms, it will go into the soil well enough. In weeding, you need never raise the hoe more than a couple of inches above the surface on your backswing. As often as not, I let the hoe scrape or scuffle right on the surface as I push it ahead for the next draw, filling in with loose dirt where I have just hoed out weeds and the dirt around them.

Another trick to saving your energy is to use the hoe as a sort of cane when you are going to step ahead for the next draw-back. As you come to the end of the current draw-back, the hoe just ahead of your feet, lean on it as you step forward, then bring the hoe along. After half an acre, that leaning is luxury to your back.

If you learn to use the corners of your regular hoe skillfully, you won’t need narrower onion hoes to remove weeds between close-growing crop plants. In using the corner, you do not try to draw the hoe toward you. Insert the corner tip of the hoe between two tiny onions (or whatever) and then push at a slight slant away from the row. The little weeds come right out, and because you have better control of the hoe, pushing the blade against the soil surface there’s much less chance that you will hoe out or cover the little crop plants. Besides, pushing in this way is somewhat restful after drawing the hoe toward you farther out from the row. And mixing the two actions keeps you from tiring too fast.

Hilling with the hoe can be artful, too. You have so much more immediate control of the hoe in your hands than you do with a power tiller. You can vary the amount of dirt you are pulling up to the row to suit the size of each crop plant in the row. You can hill up an inch going past one plant and, if the next plant needs 2 inches of dirt hilled up to it, you can immediately do so by applying a bit more muscle to the hoe. Hilling should be done straddling the row, the dirt rolled in from either side to bury little weeds much faster than you could hoe them out in any way.

In hoeing pasture weeds, the blade needs to be especially sharp, because if you do the job correctly, you will expend no more than one blow per weed, slicing through the sod to sever the taproot of the weed about 2 inches down so it will not grow back up again. But even in this work, you should not swing from above your head with a mighty chop since all that energy is wasted, and you do not have good control of the hoe during such splendidly heroic swings. A “chop” from waist high will work better and is a lot easier on hoe handles. Even a bull thistle with a 1½-inch taproot should fall with one accurate blow of a sharp hoe. When I am cutting sour dock that has gone to seed, I like to use a hoe with a sawed-off handle, so I can swing it with one hand while grasping the dock seedhead in the other. When I get a handful I lay them in a bundle to carry from the field later.

It is more difficult to be accurate with a one-handed swing—it’s a little game I play to make the work more enjoyable.

~~

7 Comments

Great Article .

Thank you so much.

Jefferson City fencing

I’ve used a particular (peculiar) hoe for many years but the stores have stopped carrying it recently.I’d like a new replacement if it can still be found. It is shaped and looks like a 9-iron golf club. Any help will; be appreciated. Thanks

I bought the 4″ hoe from easy digging after I read this article and it is all they said it was, I think the best purpose for this hoe is starting a garden in tough soil or sod.

In searching for the tiniest hoe on the earth for use in the tight quarters of a winter garden hoop house, I came across the circle hoe (circlehoe.com, among other places). It comes in both long and short handles (hands and knees size) and its diameters run from 2 to 3 inches, I believe. I love this hoe, both its long and short versions. The “inventors” angled the sharpened edge of the circle quite effectively. It’s actual circular shape and small circumference give it the feel of a mere stick in your hand. I still use my regular old hoe for faster, broader between row weeding and along-row weeding, but I’m able to do some weeding more quickly and effortlessly standing up with the long handle hoe that I was having to do by hand closer to the ground, I’ve been able to slip the short handle one right quite accurately along the edge of carrot seedlings. I love this hoe.

To Shane: Yours are the wisest words in gardening—“the trick is to do it often so the weeds don’t get strong enough to need hacking. Thanks. Gene Logsdon

The type of hoe depends a lot on the growing method you use. I grow mostly in raised beds and the spacing is very close. I like the Swan type hoe for cultivating between my tight rows. You have to use it when the weeds are very small, keep it very sharp, have a blade size that fits comfortably between the rows, and have a long enough handle that you can stand up straight. It is a great tool for this kind of work, but you wouldn’t want to use it to clean the isles between the beds. Your field hoe works great for that. It covers a lot of ground in a hurry and can take on larger weeds with ease. Those are the two I use the most. Everything else seems to fall short of my expectations. Part of it is I am used to those two hoes and other hoes require slightly different motion which my body isn’t comfortable with. Thanks for the great article.

A brilliant article. I have found the same thing- old hoes brought back to life and maybe given a long new handle are superior to anything in a typical garden store. You dont mention sharpening your hoes much- I keep a simple file handy to keen up the blade every month or so. I tend about an acre of cultivated land with a hoe and I can do the whole thing in a morning, and it is lovely relaxing work. The trick is to do it often (weekly in my case) so the weeds dont get strong enough to need hacking at.